Written by Fernando Maciá

Índice

- The beginning of the end of keywords

- Indicators that have been affected

- Obvious alternatives: data extrapolation methods

- Limitations of data extrapolation methods

- What, then, are the alternatives?

- Search queries in Google Webmaster Tools

- Keywords in Google AdWords

- Analysis of internal search

- Google Keyword Planner

- Landing-page-centric models

- Conclusions

The beginning of the end of keywords

On October 18, 2011, Google announced through its Google Analytics blog as well as its Official Google Blog that the use of the search engine for users logged into Google would, from then on, be done in a secure server (SSL) environment.

This data, which for so many years had been a key factor in SEO work, was thus hidden from an initially small percentage of visits but which, over time, has been progressively increasing. Although there was speculation that this behavior was exclusive to Google Analytics and that this information could be accessed via other web analytics solutions such as Omniture, Piwik, Google Analytics Premium, or through the more classic analytics from the server log, the truth is that, Given that the encryption occurs at the source and, in addition, the results go through a redirect within the search engine itself, none of these alternatives is valid since we cannot really access the original referrer of the landing page to which the visit arrives from the search engine results page.

In September 2013, Google also extended secure search to all users, whether or not they were logged in to the search engine. This means that we are approaching a scenario where 100% of searches will be Not Provided, as other search engines have also announced their intention to implement secure search for reasons of protecting the privacy of their users.

Indicators that have been affected

The fact that we no longer have access to the searches that originated the visits coming from natural search results has affected different indicators related to SEO activity. In particular, the following:

- Keywords: Obviously, Not provided is a catch-all in which we lose the uniqueness of a multitude of specific keywords that gave us valuable clues about the users’ search intent.

- Breadth of visibility: one of the key indicators in SEO was for what total number of unique searches we had received organic traffic in a month. In theory, an optimization of a website’s architecture often resulted in better visibility – better positions in the results – for a wider variety of different searches. The clearest indicator of this improvement was that the total number of unique searches that generated organic traffic over the course of a month increased. Often, a certain minimum threshold of visits per keyword was used to rule out visits from erroneous clicks or from irrelevant results.

- Branded SEO vs. NonBranded SEO: the essential objective of an SEO campaign has always been focused on increasing the number of new visitors, i.e. users who did not include the company’s own brand or product in their query. Although there are certain sectors for which it is equally difficult to compete for branded searches (branded SEO) as well as the travel sector, Most often, positioning tries to compete for non-branded searches, at the cost of taking market share, in the form of customers who have not expressed a preference for one brand or another, away from our competitors. Knowing how much of the traffic came from branded and non-branded searches allowed the client to identify the degree of brand recognition and memorability among their target audience and to segregate how much of their organic traffic should be attributed to their investment in brand recognition (branding) and how much to expertise of your SEO.

- TrueDirect and TrueOrganic: In SEO, we have always known that part of the traffic identified by Google Analytics as organic came from users who entered the website’s own domain in the search field of the search engine, which clearly indicated the users’ intention to visit a known domain through this navigational search. Through custom segments, we could detect this type of visits through rules by subtracting this traffic incorrectly labeled as organic and adding it to the direct traffic, which is what it really was. The NotProvided prevents us from performing this correction on Google Analytics data. All visits coming from a search engine, also these navigational searches matching the domain, will be erroneously registered as organic.

- Head vs. long tail searches: the analysis of the total number of visits per keyword allowed us to classify the visibility of a Web site between generic, semi-generic and long-tail keywords. These are different keyword categories, as a newly published domain is usually initially positioned for long-tail searches, achieving better positions in more generic searches as it gains authority and popularity.

- Indicators of visit quality by keyword of origin: that is, analyzing the behavior of users according to their search allowed us to identify which searches generated the highest quality traffic, mainly through the following indicators:

- Average pageviews/session per keyword

- Average dwell time/session per keyword

- Bounce rate per keyword

- Conversion rate per keyword

- Market share or penetration by search

Obvious alternatives: data extrapolation methods

Ever since Not provided searches started appearing in web analytics, analysts and SEOs have been trying to find alternatives to identify the keywords behind this generic expression.

Some early methods relied on extrapolation of data. That is to say, from the visits for which we did know the searches that had originated them, we tried to take these searches as a representative sample of the total number of searches that had originated all the organic visits. So, at least theoretically, if we distributed all the visits marked as Not provided proportionally among the known searches, the resulting data should be close to reality. However, this did not provide us with any additional qualitative data. The total unique keywords remained the same and in the same proportion. Only the number of visits attributable to each search varied. In practice, not very useful.

Based on this line of work, some authors have proposed more refined methods. For example, Avinash Kaushik proposed in November 2011 to extrapolate from segments of visits with similar behavioral indicators, interpreting separately the traffic of branded searches (Branded SEO), unbranded searches (nonBranded SEO), generic searches and searches long-tail in terms of landing pages, visit quality indicators, etc.

According to the method proposed by Avinash, we could assimilate that a Not provided visit had arrived with a certain keyword if it had entered the website through the same landing page and presented qualitative indicators similar to visits for which we did know the source search.

Limitations of data extrapolation methods

Although in the very announcement of the implementation of secure search on the Google Analytics blog, Amy Chang was betting that the Not provided would affect only a minority of visits, the truth is that given the increase in the use of Google services -GMail, Analytics, Google Webmaster Tools, Google+, Google Drive, etc.- the percentage of visits for which we ignore the search that originated them has only increased, usually becoming the majority reference within the section of Keywords of our web analytics system, whatever it is.

And this means that any method that tries to represent the totality of a reality from a representative sample of the same loses reliability as soon as the size of that sample decreases in comparison with the global volume of data it tries to represent.

If we assume that in the short term the volume of Not provided searches will approach 100%, any method using extrapolation of data from known data will no longer be valid due to the small sample size.

What, then, are the alternatives?

First of all, I think we should ask ourselves the following question: if search engines have started on the road to semantic search, will keywords continue to be as important as they have been to date in the search process? I am referring both to the way in which search engines will be able to interpret content semantically and also to the way in which they will be able to interpret the latent search intent behind the search expressions entered by users.

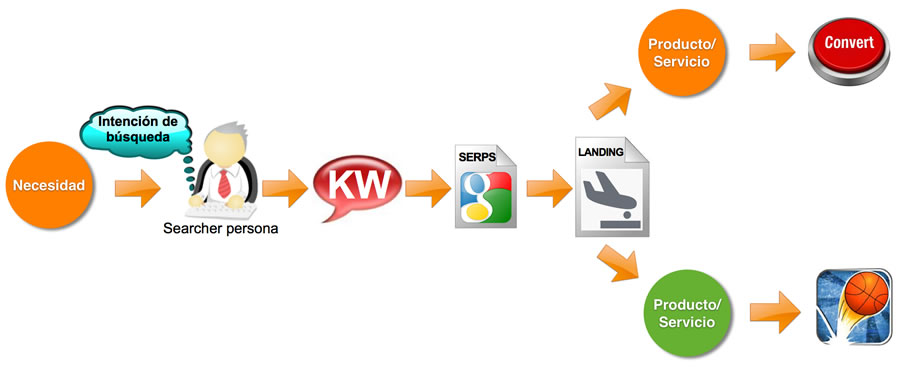

In my presentation Search Marketing: when SEO is no longer sufficient exposed during OMWeek’s SearchDays in Madrid and Barcelona in the fall of 2013, I was referring to the growing importance of the information provided by context, both from content and from users’ own searches. And it proposed some alternative methodologies to try to interpret how a need generates a search intent that the user interprets in the form of querying a search engine to access content that will either answer their need – in which case a conversion is likely to occur – or it will not – in which case a bounce will occur (Figure 1).

Let’s analyze what we can know with these alternatives and what their limitations are.

Search queries in Google Webmaster Tools

In Google Webmaster Tools, we have access to the most important searches up to a limit of about 2,000 per day, which is enough for many websites. We can consult the keyword data in which any page of our site was included among the results as well as the clicks obtained, data from which we also obtain the CTR.

We can consult, instead of the most popular queries, the entry pages. From this data, we can identify which searches resulted in visits to which landing pages.

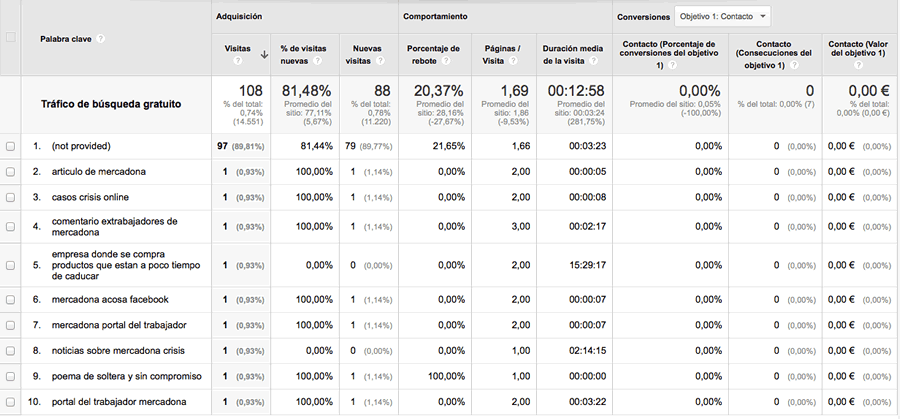

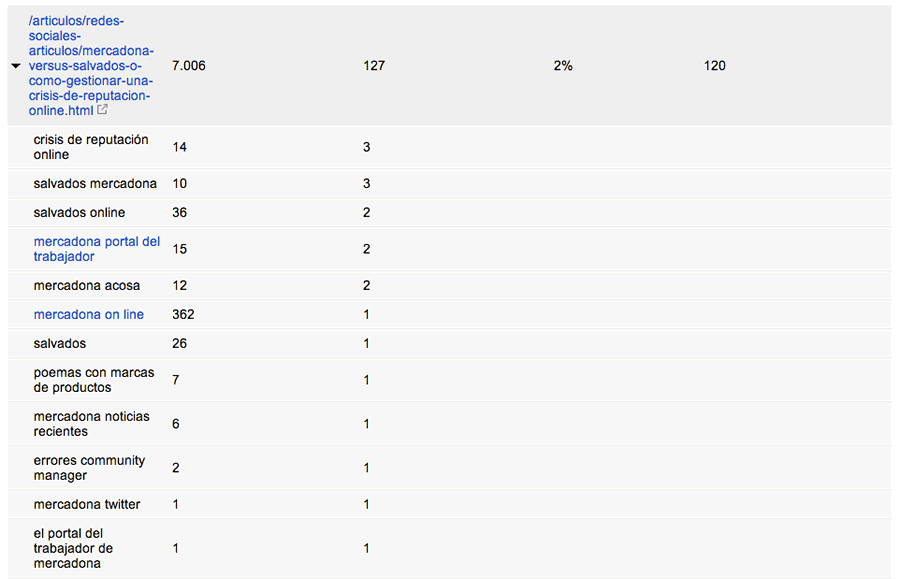

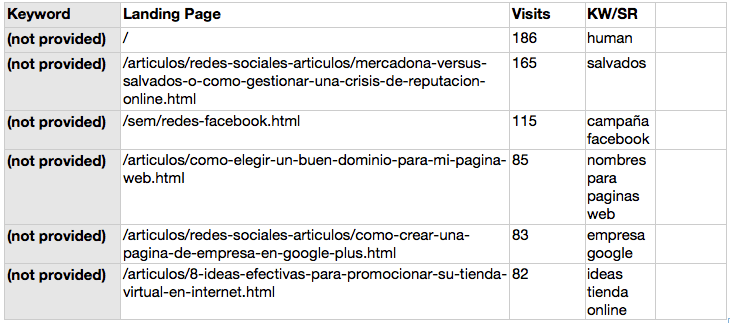

For example, if we analyze for a given period the organic traffic that reached the Human Level website landing on our post about the online reputation crisis suffered by Mercadona after its mention in the television program Salvados, we can see that it received 114 visits. We go to Behavior > Site Content > Landing Pages and segment by Free Search Traffic. Next, we select the entry page we are interested in and apply Secondary dimension > Keyword. We see that no less than 97 of these 108 visits were Not provided, that is, we do not know the keywords that originated 90% of the visits to our website through this page:

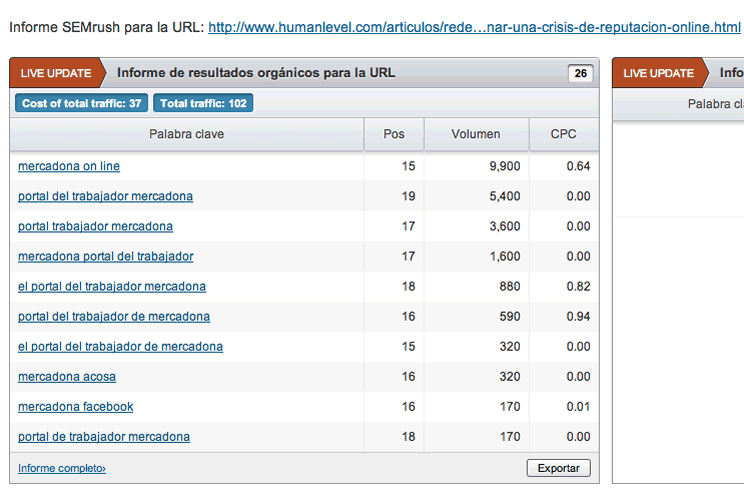

If we analyze the same page in Google Webmaster Tools popular queries for the same period (we select Search Traffic > Search Queries > Top Pages and use the Filters to find the entry page we are interested in):

We see in Figure 3 that GWT records a slightly higher number of clicks than the total number of visits recorded by Google Analytics (127 vs. 108). This is due to the different ways in which each tool collects data (GWT at the time the information is presented to the user and the user clicks on the link on the results page and GA at the time the landing page is displayed in the user’s browser, plus other factors such as the time setting of each tool, etc.) In general, GWT should record more clicks than GA.

What is striking about this comparison is that, although GWT records the total clicks and total impressions we have achieved for a given page, it only records the top queries. Therefore, the sum of clicks recorded by the tool for each keyword separately does not match the total clicks recorded for the total number of queries that generated clicks on the landing page. And that is why the queries that appear in Google Webmaster Tools do not match 100% with those that we can see in Google Analytics, although they keep a certain degree of similarity (some of these searches seem to be registered at different times of refinement of the same search, for example, “poems with product brands” in GWT and “poem of single and uncommitted” in GA, which leads us to think that in searches where successive refinement behaviors occur, the search recorded by both tools varies (GWT would record the former, while GA would record the latter).

Limitations of Google Webmaster Tools

The limitations of Google Webmaster Tools are clear:

- It has a limit of around 2,000 main searches per day. Clicks recorded beyond these two thousand searches are recorded, but not the searches that generated them. In any case, this limit may not be a handicap for many businesses that are below these figures.

- We can only access data for the last three months. This is a limitation that we can solve to some extent by periodically downloading data from GWT. Something we can automate using Python.

- There are clear differences between the keywords registered by GWT and GA, due to the different time at which the search is registered (first search vs. refined search).

However, and given that no personal data is reflected in GWT (all information is aggregated), we could think (or at least hope) that in the future Google will remove the limitation to show only the main searches and the limit of two thousand daily queries, so that it will show us data much closer to what we have lost in Google Analytics.

Keywords in Google AdWords

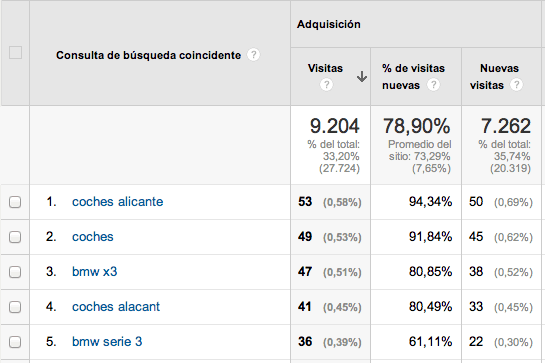

One of the sections of Google Analytics where we can still see the actual queries that generated traffic to our website is the Acquisition > Keywords > Paid > Matched search query .

If we want to get a little more relevant information, we can select as a secondary dimension Landing Page and then we could see how the traffic from each search has behaved when landing on the landing page. Qualitative data such as conversion rate or Value per visit will tell us a lot about whether we should intensify our efforts to achieve better organic positions for those keywords.

If we employ the same landing pages for our SEO and PPC strategy, this should give us valuable information about which “keyword/landing page” pairs generate the most value. While this does not tell us which visits came naturally to those pages, it does help us to target their relevance so that they rank better for those better performing searches.

If, on the other hand, we manage groups of landing pages specifically for PPC, we can still leverage the information to identify the areas of strength that are making those landing pages perform well in PPC and apply the same criteria on our organic traffic entry pages.

Avinash Kaushik proposes a custom report for Google Analytics with which we can break down the actual searches that users used before clicking on an AdWords. We can separately analyze searches that were matched by broad, phrase or exact match.

Limitations of Google AdWords

The main limitations of Google AdWords are as follows:

- Obviously, the first one is that we won’t have any data if we don’t invest in Google AdWords, so the cost would be the first one.

- Secondly, the behavior of traffic coming from AdWords is not entirely comparable to traffic coming from natural results.

- Third, a PPC campaign usually requires working with perfectly coordinated groups of keywords, ads and landing pages. We will need to do some extra work to identify which strengths of our PPC landing pages are transferable to our SEO landing pages.

Analysis of internal search

One of the places where we can continue to see what users are searching for is in internal search on our Web site. This information is available in Google Analytics, under Behavior > Site Searches > Search Terms. However, you must first configure the tracking of internal searches by the tool from Administrator > VIEW > View settings by activating the corresponding option in Site Search Tracking.

The value of this information will be more or less relevant depending on the size of the Web site. If we are talking about an e-commerce with dozens of product families and thousands of references, it is more likely that users will use the internal search engine without this being an indication of a bad architecture or unusable navigation.

This information can give us ideas, for example, about:

- What users expected to find on our website and do not identify in the menu a faster way to navigate to such content.

- Pages that do not meet users’ expectations, if we activate Home Page as a secondary dimension.

- Spelling errors when naming certain products, categories, brands…

- Taxonomies preferred by users when specifying categories or products in their searches.

- Post-search behavior quality indicators, if we activate Landing Page as a secondary dimension.

Limitations of the internal search

User behavior once on a website is completely different from search engine search activity. The conclusions we can draw from these analyses should not be extrapolated beyond interpreting navigational shortcomings or discovering search patterns.

Google Keyword Planner

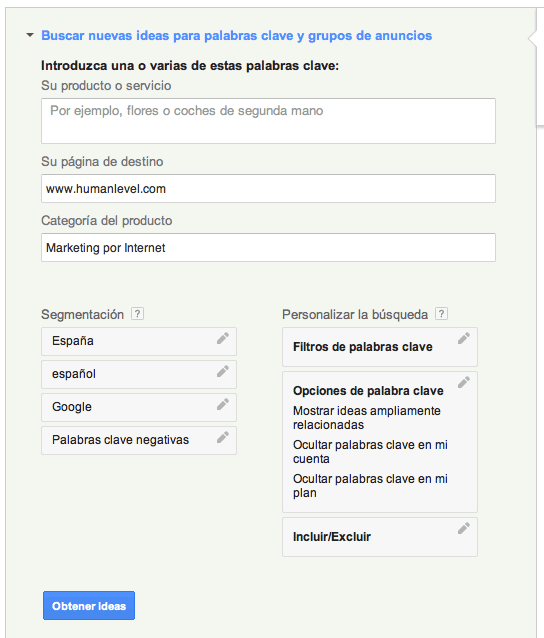

We can use the Google AdWords keyword suggestion tool to discover which are the most popular searches that Google relates to my content in a given geographic area.

To do this, I can start from Keyword Planner > Search for new ideas for keywords and ad groups:

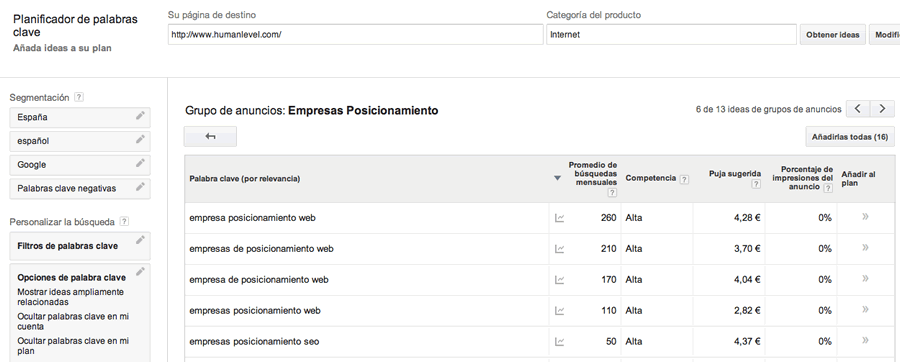

When I click on Get Ideas, Google will return the concepts that the search engine understands that, related to my content, are at the same time popular searches for the users of the geographic and language segmentation I have configured. For example, some ideas on how users would search for a positioning company:

This way I can know how I can further optimize my content to achieve better positions in the most popular searches.

Limitations of Google Keyword Planner

Again, the tool tells me which keywords I should optimize my pages for, but not how many visitors actually arrived with those searches. Although we must assume that if we achieve a good positioning for these searches, we will increase our CTR for them each time (which we can check in Search Queries in Google Webmaster Tools).

Landing-page-centric models

One of the most interesting approaches to the analysis of what lies behind the Not provided has come from Iñaki Huerta, who proposed a “landing-centric” model. I recommend reading Iñaki’s post as it seems to me a quite reasonable approach to work by pairs or sets of entry pages/associated keywords. The post also provides methods to facilitate a more intuitive and quicker identification of entry pages with their associated keywords in Google Analytics.

What Iñaki Huerta’s methodology does not solve -as no other described method does- is to unequivocally identify the keywords that originated the visits that accessed the website through those entry pages, no matter how much effort we have made to focus and position those pages in the most relevant search engines. keywords that we have assigned to them as a visibility target.

It is really difficult for a piece of content to rank exclusively for one or two keywords, no matter how targeted that content is.

In line with this “landing-page centric” model, at Human Level Communications we have proposed a methodology that tries to address this problem from another perspective. The starting points are as follows:

- A page usually ranks for more than one keyword.

- A page is visible in the SERPs when it occupies top30 positions.

- The highest probability of traffic can be attributed to the pages that occupy the best positions for the most popular searches.

With these starting points, we came up with the idea of crossing data from two different sources: Google Analytics and SEMRush.

The method we propose is as follows:

1. Obtain organic traffic Not Provided in Google Analytics: for which, we apply segment Organic Search Traffic, select in Acquisition > Keywords > Organic and click on Not provided.

1.2. We export in CSV or Excel format that we open or import in Excel or Numbers.

2. Obtain keywords where we appear in top20 positions with SEMRush: to do this, enter the domain to analyze and go to the Organic Keywords report.

3. We match Landing Pages and keywords through a vertical search: this is to find, for each landing page in our Google Analytics Not Provided tab, the most popular and highest ranked keyword for which that page is ranked, according to SEMRush.

3.2. We enter a formula that will look up each Analytics URL in the SEMRush data tab. When there is a match, it will populate the field with the keyword corresponding to that entry page.

3.3. The formula for Numbers is:

=CONSULV(search_value;search_matrix_in;column_indicator;[ordenado])

3.4. The formula for Excel is:

=BUSCARV(search_value;search_matrix_in;column_indicator;[ordenado])

4. We could take this method further by proportionally distributing all the Not provided visits among the multiple keywords for which a specific landing page is positioned in direct proportion to the popularity of that search (a data that SEMRush provides) and inversely proportional to the position we occupy for it (an approximate data that SEMRush also provides).

Limitations of our model

It would seem very nice if this model worked perfectly as described above. Unfortunately, it also has its limitations:

- SEMRush only detects top20 positions, so we will not be able to know for which other keywords a URL is positioned below that limit.

- SEMRush cannot comprehensively detect all the keywords for which a page is ranked. SEMRush uses a sample of searches and tries to match the most relevant ones based on the content detected on the page. But the truth is that almost all pages rank for a wider variety of searches than SEMRush can detect, although it seems to us a very good starting point.

- SEMRush also does not analyze all the pages of a Web site, since some or many of our pages will not have top20 positions for some of the searches sampled by SEMRush.

For example, for the URL analyzed above about Mercadona, these are the keywords and positions extracted from SEMRush:

In which we miss keywords that are present in both Google Webmaster Tools and Google Analytics.

Conclusions

Although they are stimulating exercises in reflection and in many cases can help us to better understand the searches with the greatest potential and even the search intention of our users, the truth is that this data can only be returned to us by those who took it from us.

My best bet would be for search engines to share the data recorded in the SERPs themselves through Google Analytics, but without sampling or limits and in an exhaustive manner. In this way, they would be providing us with the market knowledge we need without compromising user privacy in any way.

And, in any case, we should ask ourselves, to begin with, if in the universe of semantic search towards which we are heading, the concept of keyword will continue to be valid. The searches entered by users on mobile terminals, as their use increases, will be different from those entered on a physical keyboard. And these will also be different when voice interfaces become more widely used, as we will be dictating much more specific searches free of the hassle of typing. And in the face of successive search refinements such as the example given by Google for Hummingbird (Who is Leonardo diCaprio? > When did he get married?), which keyword would be registered? Would it make any sense?